- richard@klipopmekaar.co.za

- Certified organic rooibos

- Direct from the farm

The Botany of Rooibos

Research by Gerhard Pretorius, Editing by Travis Lyle

In this article, we provide an overview of the botany of rooibos tea from its earliest historically recorded use and the inception of the rooibos tea industry, up until the current marketplace as it is found in 2021.

The information provided here will enable the reader to understand the origins of rooibos tea, through its botanical profile and the development of the plant’s usage over time. For tea industry buyers, or simply for fans of the delicious red tea that we know and love (and grow and harvest on our farm in the Cederberg Mountains of South Africa), this resource should provide a lot of information that has previously either not been available, or has been found in a number of separate academic papers.

The Botany of Rooibos

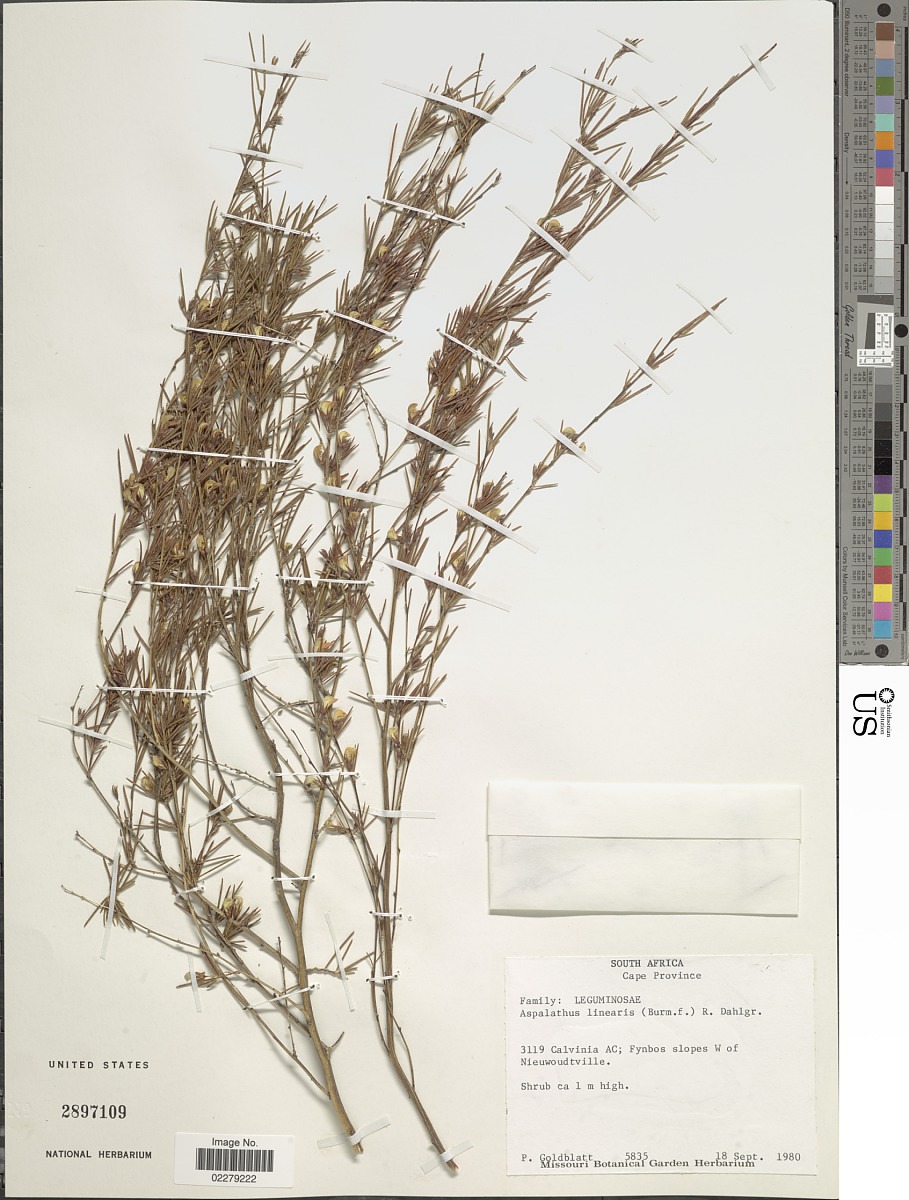

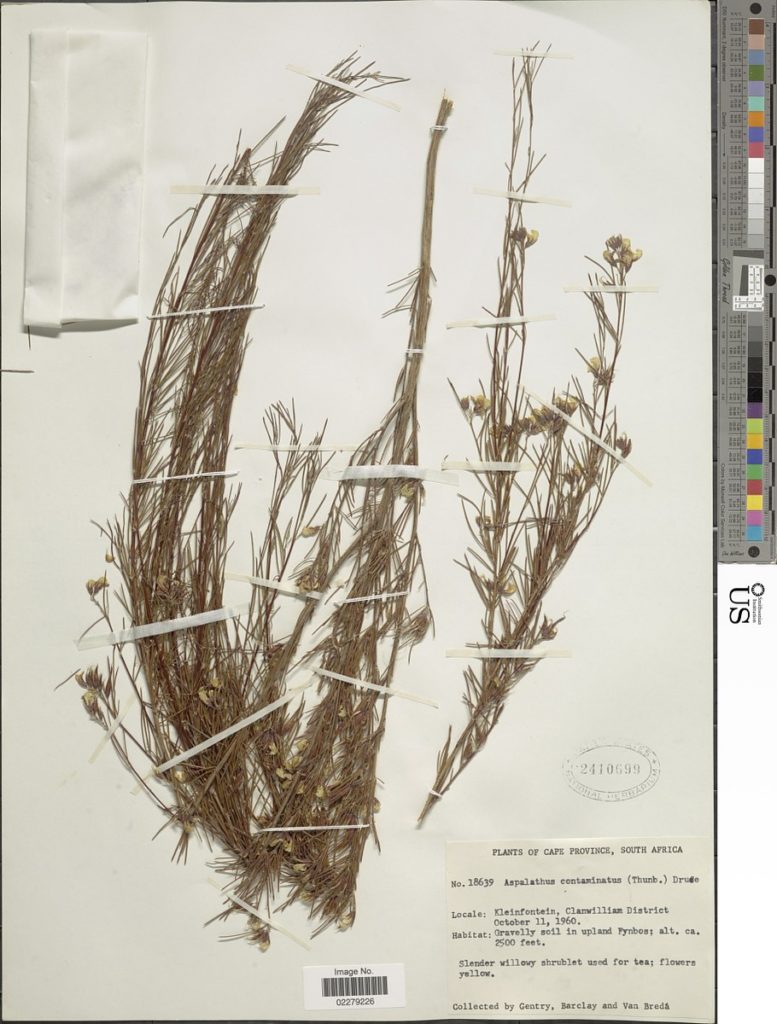

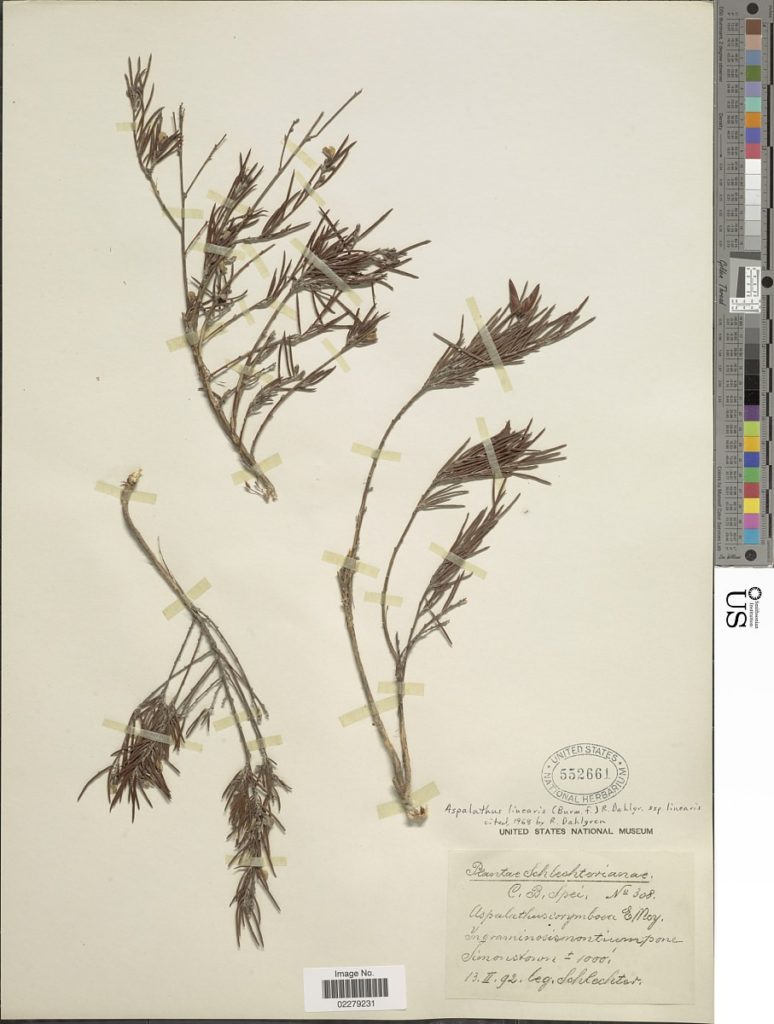

Rooibos tea is a herbal tea derived from Aspalathus linearis, a plant species endemic to the Western Cape area of South Africa. Aspalathus, a member of the legume or pea family of plants, is a genera that at last count contains 279 different species, only a few of which have been documented as being used to make rooibos tea.

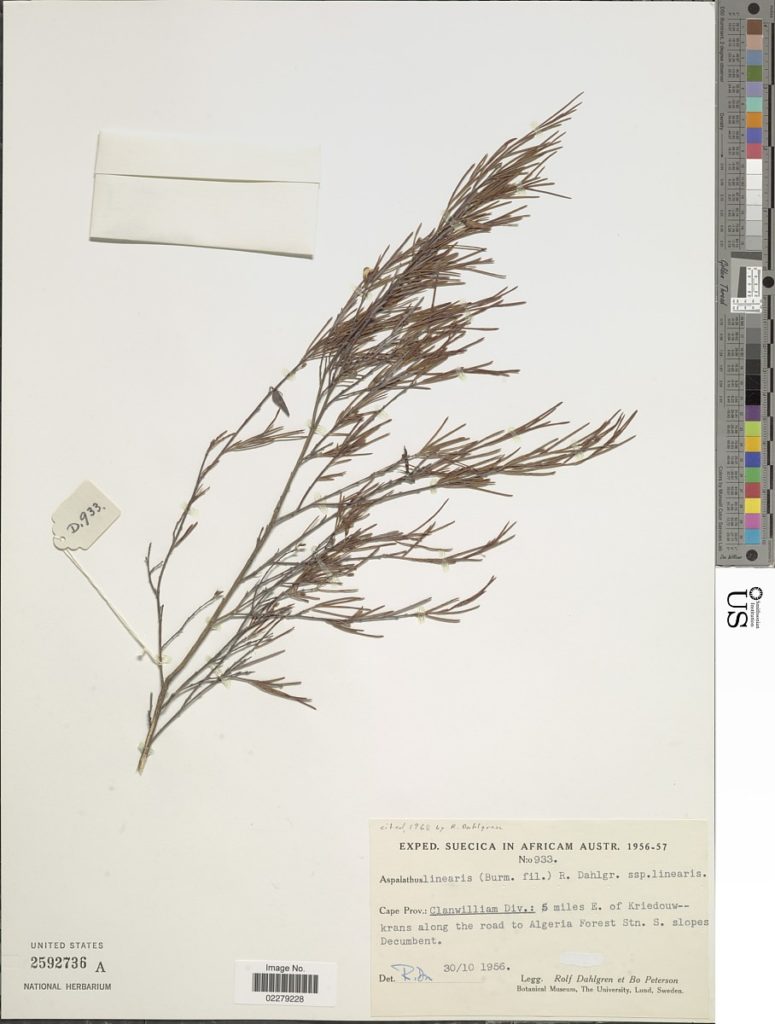

Though commercially cultivated, the crop plant has not been truly domesticated. In the wild the species is exceptionally polymorphic and thus displays a great diversity of form and characteristics, with distinct geographical forms being recognized (Dahlgren, 1968, 1988).

During the development of herbal teas in South African history, many different plant species were used, and a number of rooibos “types” were locally available in the market until the early 1960s.

Rooibos was probably known and used by pre-colonial indigenous peoples for medicinal purposes although not necessarily as a tea or for recreational purposes. It is likely that colonists, arriving from countries where tea drinking was a culture and with Asian tea being scarce and expensive, learned about rooibos from the locals and started using it as a tea.

Initially it was made from different ecotypes of wild Rooibos by the local people of the area, and slowly it began being bartered for other goods or sold.

The well-known rooibos currently dominating the market is cultivated from the ‘Nortier’ type, earlier known as the ‘Red Type’, which occurred naturally in the northern Cederberg area. It has been selected for cultivation because of the quality of herbal tea deriving from it and its manageable bushy shape, but genetic variability within the crop remains large.

There is a paucity of recorded literature on the early development of rooibos both in terms of its production and market development, but available information points to the turn of the 19th century as the inception point.

Historical Origins of the Rooibos Industry

Very little information is available about the early development of rooibos in recorded literature. Despite its current success, it appears that rooibos first originated from relative obscurity. Dahlgren (1968) states that rooibos was not mentioned in the earliest recordings of herbal teas.

Dahlgren (1988) mentions that three species of the Borbonia group of Aspalathus, namely A. angustifolia, A. cordata and A. crenata were once used as tea, as well as the similar A. alpestris. No common names were used for these plants, but because all have simple, rigid, spine-tipped leaves, the common name for the tea deriving from them was ‘stekeltee’ (ie: ‘thorn tea’ in Afrikaans).

Anecdotal mention by Swedish botanist (and student of the ‘Father of Botany’, Linnaeus), Carl Peter Thunberg, during July 1772 at Paarl, of ‘country people’ making tea from Borbonia cordata (Aspalathus was called Borbonia then) is sometimes erroneously cited as proof of rooibos tea existing at that time. It will be shown that rooibos was in fact made from Borbonia pinnifolia instead and only gets mentioned much later.

In The History and Ethnobotany of Cape Herbal Teas (van Wyk and Gorelik, 2017) the authors concluded that rooibos tea became generally known in the Cape during the period between 1902 and 1912. Rooibos was displayed at the South African Exhibition in London in 1907, lending further credence to that conclusion.

As evidenced from the testimonies of traders submitted as part of a ‘Rooibosch’ trademark case of 1909, heard in the Supreme Court of the Cape Colony (CSC, vol 2/6/1/366, ref. 783) [Cape Town Archives Repository (KAB)], National Archives of South Africa), rooibos was sold outside of its habitat, as far as Worcester and maybe even further, at least since 1902–4.

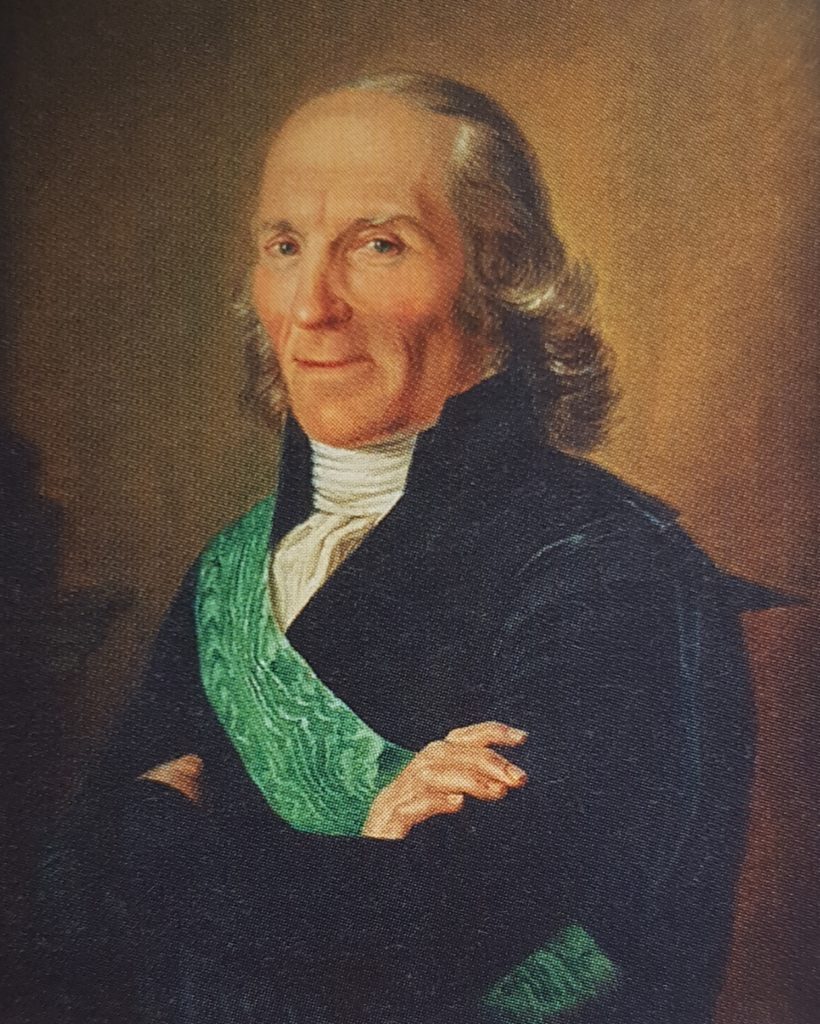

It is therefore strange that neither MacOwan (1894) nor Marloth (1909) mention rooibos tea (A. linearis) in their reviews of Cape medicinal products. Marloth undertook a botanical expedition to the Gifberg and Cederberg in 1901 (Glen and Germishuizen, 2010), and MacOwan went on a botanical trip to the Clanwilliam and Wupperthal areas in 1897 but there is no mention of rooibos tea in his later writings.

Marloth (1909) discusses Leysera gnaphalodes as the ‘Tea of the Cederbergen’, and in 1912 described the Wupperthal form of rooibos as a new species, namely Borbonia pinifolia. He stated that “The Borbonia is of economic importance, being the source of a colonial tea, viz., rooibosch tea…”. He also states: “This plant is of special interest as it supplies the ‘rooibosch-tee’, which is now so largely used in South Africa either under this name or as ‘naald-thee’ or ‘Koopmans-thee”’ (In Afrikaans, a ‘koopman’ is a merchant). According to him the shrub appeared to occur only on the Cedar Mountains near Clanwilliam and Wupperthal.

In his list of plant names accompanying the Flora of South Africa, Marloth (1917) listed rooibos tea as; ‘Rooibos tee, Rooi tee, Naald tee or Koopmans tee’, and said it was made from Borbonia pinifolia. He describes it as; “a small shrublet of the Olifants river and Cedar mountains. The twigs and leaves are cut up and fermented like the Cyclopia. A pleasant beverage, especially in hot weather, free from tannin and stimulating ingredients.”

In his updated Flora of South Africa, Marloth (1925) discusses Aspalathus corymbosa (with Borbonia pinifolia given as synonym) he states: “This shrublet yields the rooibostee (‘naald tee’) now largely used in South Africa as a harmless beverage (free from stimulating alkaloids). It is named Borbonia on the plate, as the first flowering specimens obtained from collectors of the tea possessed only leaves…”

He also calls it ‘spelde tee’ (ie: ‘pin tea’ in Afrikaans), and theorises that; “this tea,which is said to grow in abundance on the mountain slopes and commonly used by the ‘hottentots and poor whites’, may refer to rooibos tea”.

He further points out that it was used as a general health tea, as a diuretic and as a treatment for asthma.

Coetzee (1969) also provides a potential link between “reed tea” and rooibos tea. The name riettee was recorded in the vicinity of Aurora near Piquetberg, which was also known as naalde en spelde (i.e., “needles and pins”). Although the name riettee does not appear in Marloth (1917), both naalde tee and spelde tee are given as common names for Borbonia pinifolia (=Aspalathus linearis).

Smith (1966) states that “riet” or “rietjies” (ie: ‘reed’ or ‘small reeds’ in Afrikaans) is a general term applied to members of the Restionaceae that is usually found in compound vernacular names. The name riettee therefore suggests that the tea grows in fynbos (i.e., among Restionaceae), which is true for both lidjiestee (Thesium spp.) and rooibos tea (Aspalathus linearis). This reasoning led Van Wyk and Gorelik (2017) to believe that the names ‘riettee’ and ‘reed tea’ most likely referred to rooibos tea.

It was during this period that true commercialisation of rooibos probably first started as evidenced in some government correspondence at the time. During 1906 for instance PJ du Toit, Director of Agriculture in Cape Town, in a letter to the Civil Commissioner, Clanwilliam, 5 October 1906, wrote:

“I am directed to inform you that experiments are being made with Cape bush teas with a view to ascertaining whether they can be made into merchantable article. This Department has been advised that a certain kind of bush growing in your Division is used for preparing what is locally known as “Rooi Thee”; and I am to request that you will be good enough to cause about 10 lbs weight of the plant including leaves and stalk to be forwarded to this office at an earliest date.”

Botanical and Phenolic Perspective

According to Van Wyk and Gorelik (2017) the remarkable diversity of wild types of rooibos tea, all considered to be part of the Aspalathus linearis species complex, has not yet been fully explored. “The species is exceptionally polymorphic, with considerable morphological, ecological, genetic and chemical variation”.

In “The history and ethnobotany of Cape herbal teas”, they provide much detail of this and the various interpretations of different authors over the years.

Of interest here is that while only one species of Aspalathus (linearis) is concerned, it has been known at various times as A. tenuifolia, A. cedarbergensis and A. corymbosa.

Furthermore there are a number of different forms, thought by some to be the result of environmental influences such as altitude, but which are in fact genetic in nature (Van Wyk and Gorelik, 2017).

Thus according to The Conservator of Forests (1949) there was:

- True or typical Rooibos Tea – The best quality

- Rooibos Langbeen Tea; Rooibos Kortbeen Tea – slightly inferior

- Vaal Tea; Bruin Tea – inferior to No. 2

- Swart Tea – worst quality.

“These four, and especially Rooibos and Swart (or ‘black’) tea, seem to be clearly differentiated in Clanwilliam and the differentiation is very marked in the prices the various kinds fetch. … I do not think it will be possible to get more than the 8000 lbs. of Swart Tea referred to previously collected. In any case, I am not anxious to encourage further collection of that quality as there is the danger that it will be used to adulterate the Rooibos tea.”

Interestingly it seems that different types of rooibos were sold commercially as recently as the 1960’s. According to Dahlgren (1968); “Although all types of Rooibos Tea were still commercially available only a few years ago, only Rooi Tea is available today. The other types originated from wild forms that are only fragmentarily known even among the tea producers and buyers at Clanwilliam, and this knowledge will probably fade rapidly as the types are disappearing altogether”.

The Main Traditional Types of Rooibos Tea

In his revision of the genus Aspalathus, Dahlgren described the main types of rooibos tea as follows: “The professional producers of “tea” from A. linearis distinguish between the main types mentioned below:

- Rooi (red): Nortier type. This is obtained from cultivated, successively selected biotypes, which originally derive from wild forms, mainly found in the northern part of the Cederberg Mountain range (at least partly in the Pakhuis Pass area). The cultivated forms selected have fresh-green (not pale or bluish green), relatively slender leaves, erect growth, and a leafy habit. The flowers are relatively bright yellow. The tea, obtained according to the procedure described below, is reddish and has a mild aroma.

- Cederberg type. This is obtained from the wild forms out of which the cultivated Nortier Type has been selected. These forms occur mainly in the Pakhuis Mountains (northern part of the Cederberg range) and also to some extent in the mountains in the Citrusdal area (and possibly in the Olifants River Mountains).

- Rooi-bruin (red-brown): This was obtained from wild plants reported to grow mainly on the sand flats in the northern regions of the distribution area, especially in the lowlands from Pakhuis (Clanwilliam Division) northeastwards into the Calvinia Division and northwards into the Vanrhynsdorp Division. The tea produced is reddish-brown and not or only slightly coarser than the Rooi Tea; the flavour is not very different.

- Vaal (grey): This was obtained from wild forms in the mountains chiefly of the Cederberg (but probably also the Olifants River) Mountain range in the Clanwilliam Division. The leaves of the forms yielding this tea type are rather pale and greyish green, and the tea obtained is also more greyish in colour. The tea is considered to have a somewhat undesirable honey aroma.

- Swart (black): Similarly, this type is said to have been obtained from forms chiefly growing in the Cederberg Mountains, but different from those yielding the Vaal and Rooi Tea. According to information from the professional Rooibos Tea producers at Clanwilliam, the forms yielding the Swart Tea occur in rocky regions of the Cederberg Mountains. The tea is distinctly darker in colour than the Vaal Tea and has an aroma markedly different from all the other tea types. This type of tea was the first to be discontinued on a commercial basis.”

More recently, wild tea ecotypes from the northern Cederberg and Bokkeveld have been described by Malgas and Oettlé (2007), Malgas et al. (2010) and Hawkins et al. (2011).

Although some wild rooibos is still harvested and sold commercially by the Wupperthal and Heiveld small farmer co-operatives, and rarely by commercial farmers, current sale of rooibos is almost exclusively from the cultivated Nortier variety (also called the Rocklands type).

Although considerable variation may exist within some of the tea types, the following eight main categories can be distinguished:

- Southern sprouter (Cape Peninsula, Franschhoek Pass to Ceres and Tulbagh). A small plant with a prostrate growth form, somewhat hairy leaves and yellow flowers. This type was known to Dahlgren (1968) but has apparently never been used to make tea (at least not on a commercial scale).

- Grey sprouter (Citrusdal area): Erect, robust, multi-stemmed, with thick glaucous leaves; flowers partly reddish-purple. This is the source of the vaal tea described above. Although Dahlgren (1968) mentions an undesirable honey aroma, a farmer in the Citrusdal district who regularly won awards for his tea, ascribed his success to the use of this vaal tea to improve both the fermentation and the aroma of his commercial red tea (personal communication to Ben Erik Van Wyk).

- Northern sprouter (Citrusdal to Cederberg and Bokkeveld): Prostrate plants, often with the flowers partly or completely violet. This has been called kortbeen tee (Conservator of Forests, 1949) and rooi-bruin (red-brown) tea (Dahlgren, 1968), who stated that the tea quality is comparable to that of the red tea type. The rankiestee of Malgas and Oettlé (2007) agrees with this type.

- Nieuwoudtville sprouter, also known as heiveldtee or jakkalstee. It differs from the northern sprouters in the generally larger and more erect growth form. The flowers are partly violet to orange-purple. This tea agrees closely with the red-brown type of Dahlgren (1968) who apparently did not distinguish between the various northern sprouting forms.

- Red type (seeder) (Clanwilliam region to Nardouwsberg). This type is represented by the commercial form, also known as the Rocklands type or Nortier type. The habit is erect and robust, the leaves bright pale green and the flowers invariably yellow. Some populations appear to be chemically variable and may not have the typical high level of aspalathin as main phenolic compound. Dahlgren (1968) referred to wild forms of the red type as the Cederberg type (not to be confused with Type 7, which is endemic to higher altitudes in the Wupperthal area of the Cederberg).

- Black type (seeder) (Piketberg, Paleisheuwel and Citrusdal areas). This is possibly the “Black Tea” referred to by Marloth (1917) who stated that the processed tea is black in colour. The plants are typically tall, erect, sparse and slender, with the flowers partly violet in colour. It also agrees with the swart tee or black type described by the Conservator of Forests (1949) and Dahlgren (1968).

- Wupperthal type (seeder) (Cederberg region): An erect, densely branched shrublet of up to 0.8mtall with relatively small, bright green leaves. The flowers are typically bicoloured, with the standard petal and wing petals predominantly yellow but with a reddish violet (maroon) keel. Particularly noteworthy is the distinctively awned keel tip, which appears to be a unique character. This is the new species, Borbonia pinifolia, of Marloth (1912). Dahlgren (1968) treated it as a separate subspecies (A. linearis subsp. pinifolia) but did not uphold this concept in his later revision of the genus (Dahlgren, 1988). Some local inhabitants of the Cederberg have called this “bloublommetjiestee” (Smit, 2004; Smit, pers. comm.).

- Tree type (seeder) (Citrusdal area): A sparse, tall plant of up to 3–4 m high with drooping branches, relatively large, often glaucous leaves and partially violet flowers. This is probably the langbeen tea of the Conservator of Forests (1949) but is not recognised by Dahlgren (1968) as a distinct type. Malgas et al. (2010) referred to it as the saligna type. Variation studies are needed to determine the precise diagnostic value of morphological, anatomical and chemical characters as previously reported by Dahlgren (1968, 1988), Van Heerden et al. (2003) and Kotina et al. (2012).

It should be pointed out however that Van Heerden et al (2002) thought that the differences between the different types and whether they are resprouters or reseeders was not clear-cut.

Field observations by Ben Erik Van Wyk over many years have shown that Aspalathus linearis represents a remarkably diverse species complex that includes distinct regional variants, some of which are killed by fire and others not. An attempt is made below to clarify the rather confusing nomenclature that has been used for the various wild tea plants as well as the teas made from them, and is quoted from Van Wyk and Gorelik (2017):

“Fire-survival strategy in fynbos legumes were first documented by Schutte et al. (1995), who described and analysed reseeding (seeding) and resprouting (sprouting) in several genera. Van der Bank et al. (1995, 1999) studied genetic differences between seeding and sprouting populations, while Van Heerden et al. (2003) listed the wild tea types and reported on the main phenolic compounds of several provenances.

Tea made from A. pendula (Fig. 2D1,2), a close relative of A. linearis that was historically added to rooibos to improve the fermentation, was also analysed.

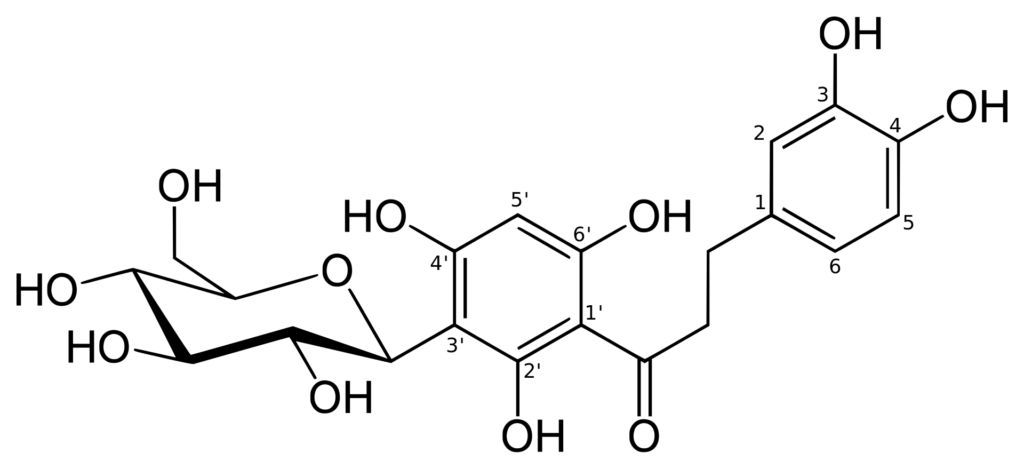

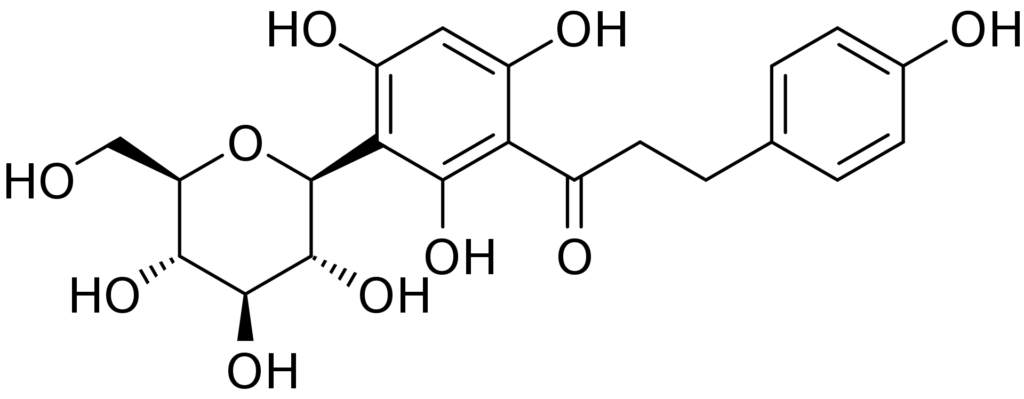

Aspalathin, a dihydrochalcone, is the major phenolic compound in the commercial red tea type (Rocklands type) but also present are another dihydrochalcone (nothofagin), together with flavones (orientin, isoorientin, vitexin, isovitexin, luteolin, chrysoeriol), flavanones (dihydro-orientin, dihydro-isoorientin, hemiphlorin) and flavonols (quercetin, hyperoside, isoquercitrin, rutin) (Joubert and De Beer, 2011).

Some wild populations contain rutin and other flavonoids (Van Heerden et al., 2003) and rutin was also reported to be the main flavonoid in A. pendula.

Traditional Knowledge and Early Adopters

In Rooibos: An Ethnographic Perspective, Boris Gorelik (2017) discusses in great detail the history of the development of rooibos in a definitive study on the subject. According to Gorelik (2017) several authors have assumed that the tea originated from the local inhabitants of the Cederberg.

Statements that rooibos tea is a traditional drink of Khoi-descended people of the Cederberg (and “poor whites”) are correct but it has not been possible to trace this tradition further back than the last quarter of the 19th century.

Unfortunately, there are no earlier ethnobotanical records of rooibos and no Khoi or San vernacular names have ever been recorded for it. All the common denominations of the Aspalathus linearis plant that have been established to date are of Afrikaans, Dutch or English origin.

These are rooibos, naaldtee, swarttee, koopmanstee, bossiestee and bush tea.

Gorelik (2017) examined all available data on rooibos and concluded that no record has so far been found to support the idea that the indigenous people made tea from rooibos. He distinguishes between knowing a plant, knowing its uses and the method of using it.

While there is no data directly disputing the assumption that the Khoi and San people had traditional knowledge of rooibos, that can not be construed as meaning that they made tea from it by infusion or decoction for leisure purposes.

For one thing they did not have the knowledge of boiling water until colonial times. Gorelik (2017) states: “We have no direct evidence that the San utilised the rooibos plant in the precolonial era. If we suppose that they did, it could have been in a way completely distinct from making a hot beverage. Archaeologists and anthropologists have not reached a consensus on whether the San consumed infusions or decoctions (like rooibos tea) in the precolonial era”.

It could be that they had medicinal uses for rooibos, but if so they had no name for either the plant or the remedy. A study by the Department of Environmental Affairs relating the traditional knowledge of rooibos (2014) states that traditionally rooibos was used as a beverage with medicinal and therapeutic properties to soothe digestive disorders, reduce nervous tension and promote sound sleep but references are lacking.

Persistent mention in literature does however indicate that rooibos was initially used as an alternative to Asian tea because it was cheap, harmless, soothing and had various therapeutic characteristics that were attributed to it.

Van Wyk and Gorelik (2017) speculate; “Could it be that some of the indigenous teas were ‘discovered’ as part of a general commercially motivated survey (perhaps inspired by traders, missionaries and colonial commissioners) to find alternatives for the expensive imported black tea?”

There are many historical records of tea-drinking during colonial times. It was apparently a well-established custom even among the poorest settlers (Gorelik, 2017). Examining various sources he states: “Hawkers played a crucial role in the economy of the Cederberg and the surrounding areas, at least from the second half of the eighteenth century, peddling essential wares, such as food, clothing or medicine. Possibly, they also offered Chinese tea. The goods were sold for money or bartered for farm produce.”

The first shop in Clanwilliam opened in 1822 and Asian tea, Camellia sinensis, was sold there. Later court records of theft in the area shows that it was also stocked in other shops.

However Asian tea was expensive. Gorelik (2017), referring to Eric Rosenthal’s study of the South African tea industry (Date obscure, 196?) states; “The inhabitants of the remote areas of the Cape Colony, like the Cederberg, could not afford to drink imported tea regularly. Viable Camellia sinensis tea plantations in South Africa were only founded in the late 1880’s and could not satisfy the demand. The rooibos infusion, as we know it, would have been a palatable, easily available alternative to those people in the region who enjoyed Chinese tea”.

Rooibos was also used more as a decoction than an infusion and it was common for locals to have a pot on a stove or fire brewing all the time. Some people still do this today.

How Was Rooibos Produced in the Early Days?

Before commercialisation, rooibos was mainly used by coloured people and poor whites as a cheaper alternative to Asian tea, and when trading started locally it was also produced by coloured people from wild rooibos populations.

Initially farmers and harvesters burned the areas where wild rooibos occurred to increase its growth and production. While burning is now much more controlled by legislation this practice sometimes continues with coloured communities, and wildfires do lead to increased rooibos populations for a number of years in those areas.

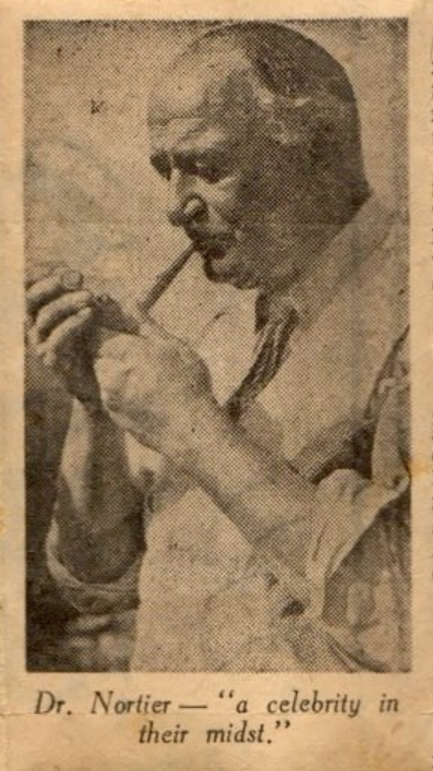

If carried out incorrectly this practice can lead to veld degradation and erosion, as was reported by Dr. Pieter Le Fras Nortier, who was the district surgeon and naturalist in 1931.

He remarked: “It is generally held by farmers that periodical burning of veld is necessary to encourage tea and buchu for a few seasons as these would otherwise be choked and stunted by other shrubs. Undoubtedly this is the most important urge for veld burning”, (Gorelik, 2017).

Of course today we know that the fynbos vegetation that rooibos occurs in requires fire at certain intervals, and that rooibos naturally flourishes after fire until succession allows other plant species to dominate. The danger lies in too frequent fires, the wrong season or weather conditions.

It was in these very early days of the rooibos industry that an immigrant to the area, Benjamin Ginsberg, whose family were part of the Popoff tea trading empire well-known in Russia – established himself as a merchant and began to take an interest in the local plants used to make tea. It was Benjamin that began to encourage farmers to collect and process rooibos on a large scale, and Nortier who was the one to propose a cultivated variety of rooibos to be grown on appropriately situated land.

Nortier worked on the cultivation of rooibos in partnership with Oloff Bergh and Wiliam Riordan, with Ginsberg’s encouragement. The first trials were carried out on the farm Klein Kliphuis (14 km northeast of Clanwilliam) and Varkfontein (west of Cederhoutkop) in the Pakhuis mountains (Gorelik, 2017)

Our farm Klipopmekaar has its location alongside the Klein Kliphuis property, where Pieter Le Fras Nortier was the first person to experiment with and cultivate a crop of rooibos in 1930, and is also a neighbouring property to Varkfontein. It’s here that we cultivate the ‘Nortier’ type, in the area of its genetic epicentre.

Nortier and Ginsberg: Rooibos pioneers

Nortier collaborated with members of the coloured community to obtain rooibos seeds which were scarce and expensive (£5 per matchbox full, about R7000 today). The seeds are tiny and are very difficult to spot and collect from the soil where it lands after the pods split open and shoot them out.

The seeds were collected in the Rocklands and Grootkloof areas with the help of coloured workers who were paid by the amount brought in. A couple, Hans and Tryntjie Swart realised that there was a type of ant that collected the seeds and stored them underground. They would dig out the nests, remove the seeds and deliver them to Nortier.

The variety developed by Nortier (so-called mak tee) is more erect than the semi-prostate wild rooibos and is a re-seeding type that does not survive fire but coppicing (although it can germinate under the right conditions fairly quickly).

According to Gorelik (2017) the cultivated type could live from 5 to 15 years, however around five years is the maximum today. Rooibos from wild plants could be harvested for 50 years or more from some plants.

It is said that Nortier did not capitalise on his invention but shared it freely and was just satisfied that a problem had been solved.

Processing of rooibos was traditionally done by beating the cut material on a flat rock using a wooden pole or club, or a wooden mallet called a “moker” which is a Dutch word meaning to “beat” something. The club could be made of hardwood such as Dodonea viscosa (sand olive) and a mallet was usually made from Olea europaea subsp. europaea (wild olive), or Protea nitida (Waboom or Wagon Tree). There is an example of a moker on display in the Clanwilliam museum. The older people in the Wupperthal and Bokkeveld areas also say that an axe was used to cut the harvested material into smaller pieces.

The bruising caused the extraction of fluid from the leaves, which started an oxidation process turning the leaves brown.

Gorelik (2017) states that one f the earliest descriptions of the technique for making rooibos tea was found in a letter from Assistant Conservator of Forests, Western Conservancy to Chief Conservator of Forests in Cape Town in September 1907, where he said: “The present method preparing tea from “Rooibosch” appears to be as follows: The branches are first cut and collected, the leaves are then beaten off, moistened and rolled up tightly in sacking for a few days. After that they are dried in the open air and the tea is ready for market.”

Another early description of processing rooibos dates to 1926 when an employee of the Elsenburg School of Agriculture visited Nieuwoudtville and the Suid-Bokkeveld to the south of it and wrote:

“The twigs with their needle-shaped leaves are collected from the bushes as they appear scattered along the mountain slopes. In some parts it is held that the twigs should on no account be cut off by knives, but must be plucked off by hand. These twigs and leaves are afterwards chopped up by a chaff cutter, stamped down by a heavy mallet, allowed to “ferment” or sweat for some days in tightly packed and covered heaps. During this fermentation, the colour of the twigs and leaves changes to a reddish brown colour according to the species of bush used. The tea is then allowed to dry and is bagged and sold, usually to local shopkeepers, who re-grade and sift it where necessary.”

Benjamin Ginsberg’s (who is credited with first commercialising rooibos, as discussed later on in Part II of our series of articles) son, Henry Charles (Chas) Ginsberg, became known as the “Rooibos King” for his contribution to domesticating rooibos and turning it into a major agricultural crop. To this day, members of the Ginsberg family remain significantly involved in the rooibos tea industry.

The Rooibos Industry: First Steps

In the early 1940s, he laid out the first dedicated large-scale rooibos plantations on three farms: Die Berg, Môreson and Stillerus. He produced up to 750 bags per season on small parcels of mountain slope, and later produced 6 500 bags annually.

By 1950, half of all Rooibos produced was being grown on these three and a third to half of all seed was being collected there.

He also developed new technologies for drying the tea and introduced more sophisticated cutting machinery used by the tea industry in India at that time (Ginsberg, 1976 and the South African College Schools Old Boys’ Union website).

The basic process of harvesting and processing rooibos has remained the same, albeit at larger scale and with the assistance of modern agricultural implements and tools.

Even today the rooibos is harvested by cutting off the branches and leaves with sickles (industrial tractor driven cutting machines are used in some cases), cut into small lengths (depending on the grade required), oxidised in packed heaps until ready, and dried in the sun in tea courts. At Klipopmekaar, our rooibos is hand-harvested using sickles, processed on site and dried in our tea court in the heat of the Cederberg summer.

In its 2013 “Application for protection of the name “Rooibos” in terms of Section 15 of the Merchandise Marks Act, Act No 17 of 1941” which is also the document used in the application to the European Union for a Geographical Indication (GI), production of rooibos is described as follows:

- Rooibos producers must adapt their land management and cultivation

practices to the harsh conditions of the region. - To avoid wind and water erosion they use the following practices.

- Planting across the slope and contour of a production area.

- Planting cereal cover crops to protect young Rooibos plants.

- Ensuring that there is sufficient vegetation cover at all times to prevent soil

erosion by wind. - Alternating natural vegetation strips of at least 10 m wide with cultivated

Aspalathus linearis strips of no more than 30 m wide. The strips must be

oriented across the prevailing wind direction that causes wind erosion. - Applying intercropping by alternating planted and unplanted rows from one

production cycle to the next or resting the soil for a minimum of two years

before replanting to Aspalathus linearis. - Establishing cover crops during rotational periods to help restore the

organic content of the soil and provide a healthy environment for desirable

soil microorganisms. - Favouring rolling or brush-cutting when clearing areas for cultivation

instead of ploughing. - Ploughing only when there is enough soil moisture to prevent erosion.

- Employing conservation tillage techniques to promote organic content of

soil, as well as to retain vegetation cover and improve the moisture content

of soil.

Thanks for reading about the botany and history of rooibos; we hope you’ve enjoyed our journey into this fascinating plant’s origins. For further reading, we can suggest our article ‘The History Of Rooibos Tea‘.